You can take that question any way that you want to. A good portion of Freemasons will scoff at the very idea, actually. That’s okay with me, because it is a question, not a thesis or a positive statement. The question occurred to me when I was spending time with the document/object that is the subject of this post. It is a question worth pursuing, I think, even if the answer is a shrug, or a big red zero. Many will probably be with me, however, in the supposition that such will not the the total answer, almost no matter what.

First off, I want to clarify and simplify. I belong to a so-called “mainstream” Masonic Grand Jurisdiction—I prefer the more current term of State Grand Lodge, a non-loaded distinction from Prince Hall Grand Lodges—and so when I make first person references, whether singular or plural, I am referring to the Masonic constellation to which I belong. And I will refer to other Masonic obediences or groups in the third person. That’s just language. I don’t in any way mean for this to be an “Us vs. Them” discussion, even if those are the pronouns I use. I want to explore this little document objectively; I would be sad if someone were to assume that I am approaching this from a predisposed, dismissive perspective. Just because this document comes from another Masonic obedience, one that my own tradition refers to as “Clandestine,” again—those are the words that I have available to use. I don’t feel the need to coin new terminology for this discussion. Second, for those Masons who sniff in disgust when someone studies something that they feel to be outré, I can only assure you that I am very comfortable with the regulations and laws of my Grand Lodge. More than that, I am very comfortable with my Obligations, and I adhere to them. Even admiration for the Clandestine, if that is where this stream of thought ends up, is no declaration of any wild intention on my part. Chill.

First off, I want to clarify and simplify. I belong to a so-called “mainstream” Masonic Grand Jurisdiction—I prefer the more current term of State Grand Lodge, a non-loaded distinction from Prince Hall Grand Lodges—and so when I make first person references, whether singular or plural, I am referring to the Masonic constellation to which I belong. And I will refer to other Masonic obediences or groups in the third person. That’s just language. I don’t in any way mean for this to be an “Us vs. Them” discussion, even if those are the pronouns I use. I want to explore this little document objectively; I would be sad if someone were to assume that I am approaching this from a predisposed, dismissive perspective. Just because this document comes from another Masonic obedience, one that my own tradition refers to as “Clandestine,” again—those are the words that I have available to use. I don’t feel the need to coin new terminology for this discussion. Second, for those Masons who sniff in disgust when someone studies something that they feel to be outré, I can only assure you that I am very comfortable with the regulations and laws of my Grand Lodge. More than that, I am very comfortable with my Obligations, and I adhere to them. Even admiration for the Clandestine, if that is where this stream of thought ends up, is no declaration of any wild intention on my part. Chill.

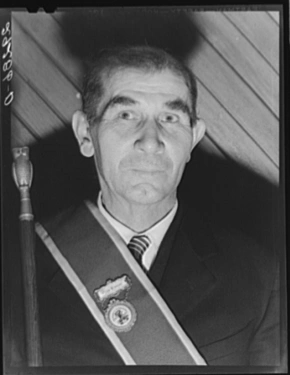

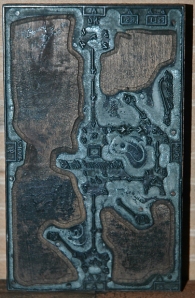

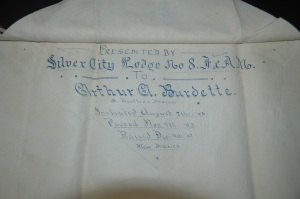

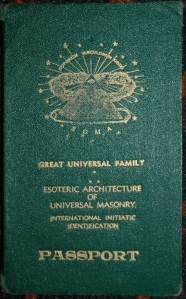

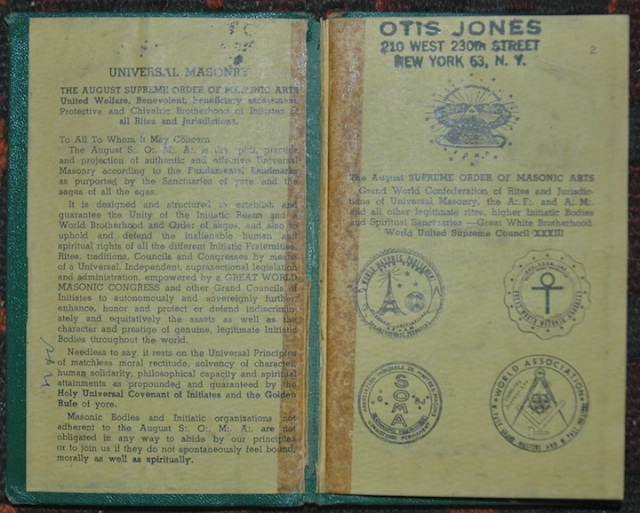

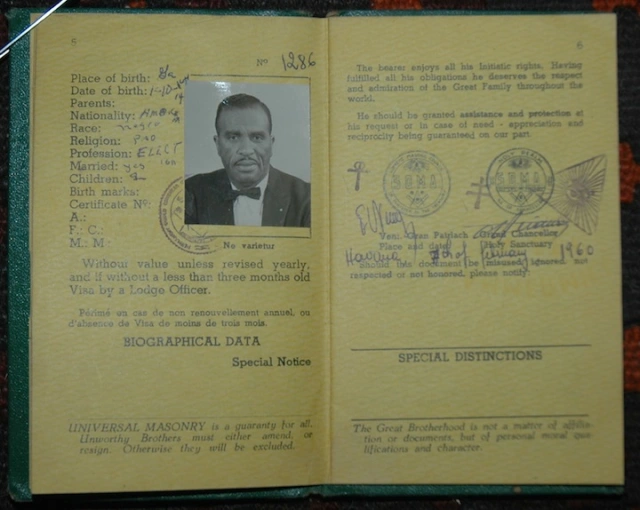

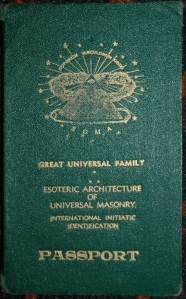

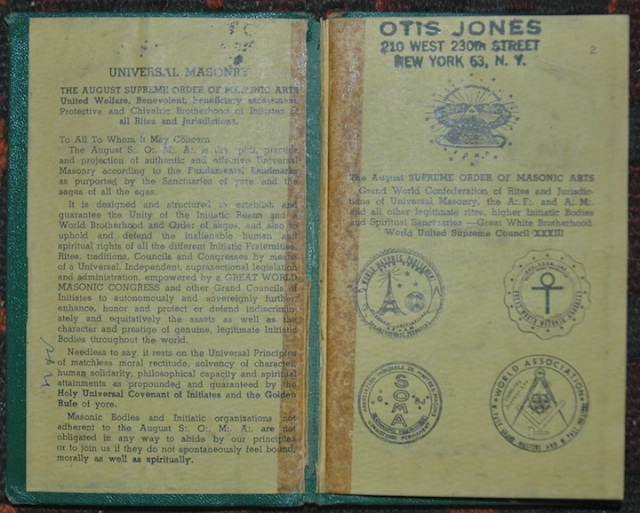

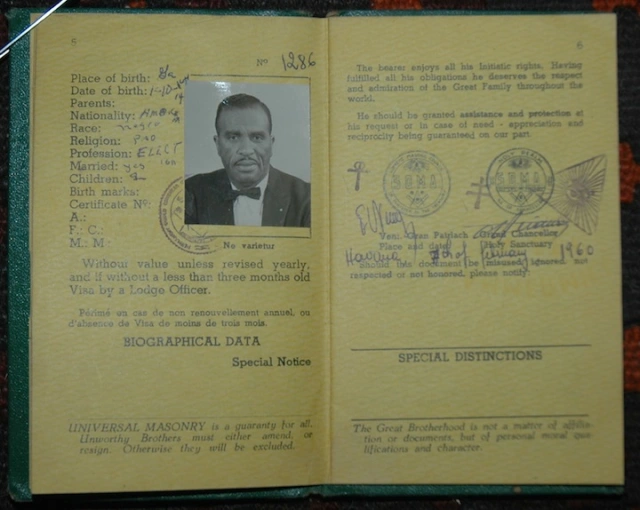

What we have here is a membership document for a gentleman named Otis Jones, who belonged to The August SUPREME ORDER OF MASONIC ARTS, hereafter referred to a SOMA. (Which is very clever on their part.) It dates from 1960, and hails from Brooklyn, NY, where Mr. Jones belonged to Mount Olive Lodge #10, under the jurisdiction of the King Solomon Grand Lodge. It is, so you see marked on the front cover, a Masonic PASSPORT for this gentleman. Which is a cool sort of idea. Anyone who belongs to the Moorish Orthodox Church of America (or even some in the MST of A) will feel their ears start to perk ’round about this point. On the title page it is written:

Grand World Confederation of Rites and Jurisdictions of Universal Masonry, the A:.F:. and A:.M:. and all other legitimate rites, higher Initiatic Bodies and Spiritual Sanctuaries—Great White Brotherhood. World United Supreme Council XXXIII.

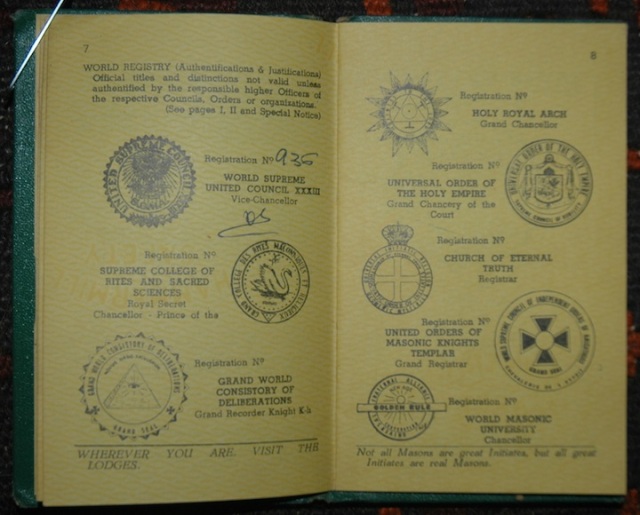

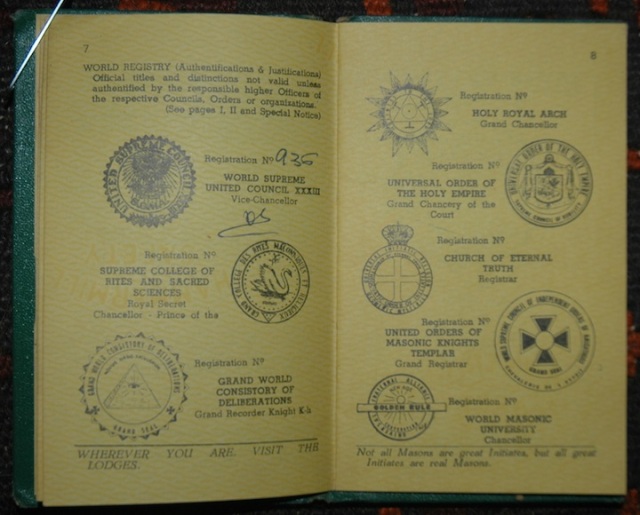

The document is absolutely loaded with seals, sigils, stamps, initials, official marks, and other bits of officialdom. By the looks of it, SOMA was the umbrella for a pretty wide-ranging group of organizations, both here in North America and abroad. There’s quite a bit of French here and there throughout the passport, and as you can see above, one of the seals of one of these organizations sports an Eiffel Tower. Now, honestly, this could mean one of a few different things.

- It could, to be honest, be a lot of smoke: Sometimes on organization may pump up its stature and credit by claiming international association and jurisdiction, even if that is shaky at best. This is a common behavior, and y’know…okay, big deal.

- It could be a matter of lingua franca. This might tie in a little bit with possibility number one, the supposition that it would be necessary and warranted to be using the international language in this document. (For those raising an eyebrow, in times past it was French and not English that was considered the international language. The term itself, for heaven’s sake, literally means “The Frankish tongue.”) You will still find a good deal of French in your US Passport, for that matter. So this might have been done to underline the nature of the thing as a genuine passport, in its own right.

- It could be a nod to French Masonry. Freemasonry in France has long been the most “liberal” (a very imprecise term) in the world. I won’t go into it here, but the French (and Belgians, I think) have always been off in left field from the rest of the world (read: UGLE-affiliated) of Masonry. And thus, most of the world actually holds the preponderance of French Masons as Clandestine.

Not being a part of this organization, or constellation of organizations, I must admit to some difficulty navigating the import of some of this. But from what I gather, as Mr. Jones joined various bodies under the SOMA umbrella, his passport would have been updated with a membership registration number from each, next to the respective seal. From the looks of it, Mr. Jones only ever joined the one organization, the one at the top: the World Supreme United Council XXXIII. Kind of cool, actually. I can see how this might have been a very satisfying document to have and live with, as you gathered nods from various organizations and their executives.

At the same time, there is an injunction against the mere collection of titles, rites or degrees. Each page of the passport has an aphorism or adage at its bottom. At the bottom of page 6, the holder is reminded:

“The Great Brotherhood is not a matter of affiliation or documents, but of personal moral qualifications and character.”

Indeed. This is a point that might be made in any Masonic obedience or community. We all know the Collectors, after all. I once had a guy, in all seriousness, utter the words, “It’s about getting more degrees, isn’t it?” My mouth responded with a sad, “No, it isn’t,” as I shook my head and walked away. I never really spoke to him ever again, and he since has moved away. The aphorism at the bottom of Page 5 of the passport reads,

“UNIVERSAL MASONRY is a guaranty for all. Unworthy Brothers must either amend, or resign. Otherwise they will be excluded.”

Again, worthy of consideration by anyone in any walk.

For all the cool symbols and stamps and seals, I think it really is the aphorisms or maxims at the bottom of each page that are the most particularly interesting part of the Passport. More than all the rest, which might be seen as perhaps a little overblown and postured (there’s a total of 21 different organizational seals/symbols in this little booklet…that’s a lot), the character of the organization is revealed in these phrases. Maybe it’s just rhetoric, who knows. I guess that depends on the individual member to decide and exemplify through their actions. This is true of any organization or group which has a stated purpose and philosophy, including my own Lodge and Grand Lodge. There are those who see the rhetoric of the organization to be merely window-dressing, because hey, they have big plans and ideas of their own, and it isn’t important to them that their activity or point of view is antithetical to the values of the fraternity. And there are those who take those values personally and seriously, and attend to them with vigor.

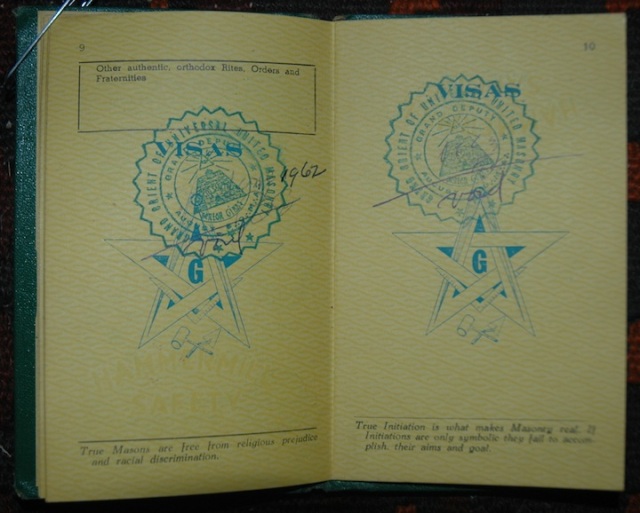

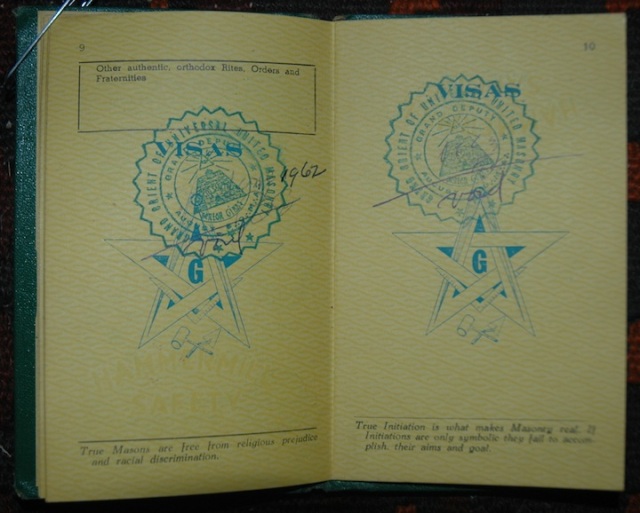

I think one of the most important and most interesting of the aphorisms is at the bottom of Page 9, seen above.

“True Masons are free from religious prejudice and racial discrimination.”

Younger Masons these days might not really know why that is a truly poignant and affecting turn of phrase. But remember, this is from 1960. The long game of the Civil Rights Movement—which stretched back to the mid 18th C—was just gaining the steam it needed to finally break through and solidify gains. In 1960, four black guys sat at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro and were refused service. That’s what was going on in the news when Mr. Otis Jones joined this branch of Freemasonry. The country was gearing up for some serious showdowns, which would develop over the ensuing years. And Freemasonry remained far, far behind the curve on all of this stuff. And in many states is still way behind!

So here we have this Passport, from a Clandestine association of Masonic obediences and organizations, and in 1960 they are putting in print the stated judgement that Freemasonry should adhere to its own rhetoric, and reject discrimination on racial and religious grounds. In this, SOMA aligned with the surging and progressive currents of the nation, in strict and utter contrast to the State Grand Lodges of the time, most of which remained in 1960 at least partially segregated, and many entirely so. And at this time, all of “Black Masonry” was considered Clandestine by the State Grand Lodges, regardless. (Today, most Jurisdictions in the US recognize Prince Hall Masonry as equal and regular. Organizations like King Solomon Grand Lodge, as well the International Masons and several other groups, are still held to be Clandestine. That is not because they are primarily African American in membership, but because they originated spuriously, and/or do not adhere to the Landmarks that we mark and observe.)

If we take this Clandestine group at face value of their maxims, however, we have before us a group that, at least in one matter, was more Masonic than our own Jurisdictions. And they were absolutely right, at least from my reading of the tenets of Masonry. Worth noting.

So I look around at some of the Clandestine groups (the honestly legit ones, not the fly-by-night lodges or the expensive degree-selling scams) and their ideas. I ask myself, “Why did they break away?” Most current Clandestine Masonic groups seem to be formed by regular “mainstream” Freemasons, probably even in good standing, who for some reason feel that their Grand Jurisdictions are not getting it right, and they set off on their own. And I would imagine that in many, many cases, they give up a great deal in order to do that. Like I said, I’m very comfortable with my Grand Jurisdiction and my obligations. But I won’t turn up my nose at the thought of examining the beliefs of others.

This Passport may not represent my accepted world of Freemasonry, but they definitely were getting something right, when my own Masonic forefathers were still laboring, at least in this matter, in comparative darkness.

This means that old entries/pages that people have visited (dare I say “bookmarked?”) won’t be there any more, but nearly all of the same objects will be viewable under the same broader headings. Also, comments left on individual entries will unfortunately be lost. Apologies to the authors.

This means that old entries/pages that people have visited (dare I say “bookmarked?”) won’t be there any more, but nearly all of the same objects will be viewable under the same broader headings. Also, comments left on individual entries will unfortunately be lost. Apologies to the authors.